Meet lab instructor Kevin Shaughnessy

By Marissa Hall, Mount student

Just by looking at his cheery smile and flannel shirt, you may not have guessed that Kevin Shaughnessy is a scientist. From the beginning of his career, he’s been one to break stereotypes. When asked to name his main field, Kevin – a lab instructor at Mount Saint Vincent University and past-researcher – pondered for a moment, and replied with a smile, “I would call myself a jack of all trades.”

Just by looking at his cheery smile and flannel shirt, you may not have guessed that Kevin Shaughnessy is a scientist. From the beginning of his career, he’s been one to break stereotypes. When asked to name his main field, Kevin – a lab instructor at Mount Saint Vincent University and past-researcher – pondered for a moment, and replied with a smile, “I would call myself a jack of all trades.”Kevin grew up and went to school in St. Marys, a small rural town in southwestern Ontario. Surrounded by nature his whole life and fascinated by wildlife, he found himself excelling at biology in high school. In hopes of later studying to be a vet at the University of Guelph, he did a co-op term with the local veterinary clinic in high school.

However, as he worked towards his goal through a zoology degree, Kevin realized that he had a bigger passion than veterinary work: research. This passion carried over into his Master’s degree in ecotoxicology at the University of New Brunswick, and beyond.

Kevin has done field and lab-based research at various post-secondary institutions throughout the Maritimes and Ontario, ranging from measuring the effect of ultra-violet radiation (UVR) on mosquito larvae survival, to studying how pulp mill waste affects the reproduction of fish. He has also notably conducted research around the Great Barrier Reef in Australia.

“Take time in life to figure out what you love to do. I knew that I wanted a career in science, but had no idea what direction I should take. I exposed myself to lots of different fields and took any good science opportunity I could for years.”

— Kevin Shaunghnessy, Senior Biology Lab Instructor

A passion for field work

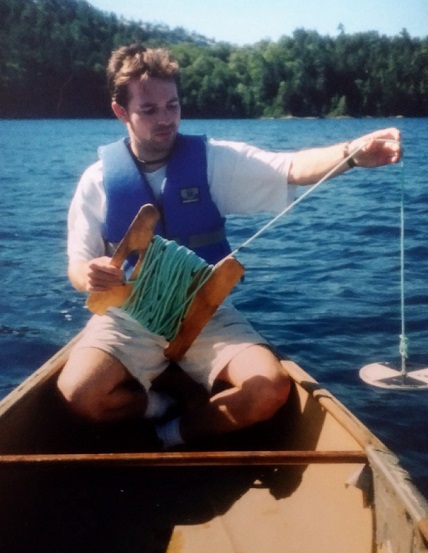

Kevin recalls his most memorable research project as the summer he spent in the Northern Ontario wilderness.

Kevin recalls his most memorable research project as the summer he spent in the Northern Ontario wilderness.

To test the effects of UVR exposure on mosquito larvae, Kevin and one of his colleagues carried out two months of field research on a small remote lake in Killarney Park, ON. A rope was tied to opposite sides of the lake from which were suspended a series of long pipes containing flasks of mosquito larvae at various depths in the water. The plan was to pull the flasks up daily and count how many mosquito larvae were still alive.

But everything is easier said than done.

“So, every day I had to jump in and out of a canoe multiple times throughout the day,” Kevin recalls. “I had to swim under water, undo some ropes and detach each flask. Then I had to hand them to my research partner, who would count the surviving larvae. Then I had to re-attach the flasks and reposition them in the water column. It was cold water too, by the way.”

“So, every day I had to jump in and out of a canoe multiple times throughout the day,” Kevin recalls. “I had to swim under water, undo some ropes and detach each flask. Then I had to hand them to my research partner, who would count the surviving larvae. Then I had to re-attach the flasks and reposition them in the water column. It was cold water too, by the way.”In addition to noting the water depth, Shaughnessy and his colleague recorded the sun’s intensity and the water’s acidity (otherwise known as its pH level).

A lot of the research and field work Kevin did was focused on the advancement of knowledge within the zoology branch of biology. Knowing how pollutants from factories affect fish reproduction can be useful in conservation acts, but there was one study that really resonated with him.

Research with a personal connection

After moving to PEI to be with his wife, Kevin took on a lab job at the University of Prince Edward Island. The study he joined involved rats with hypertension, otherwise known as high blood pressure.

High blood pressure is attributed to oxidants. Oxidants are free-floating, harmful oxygen atoms in our bodies that bind with the elements that hold us together. Much in the same way a machine will break if a part is broken off and becomes jammed, we experience hypertension as these atoms bind with our DNA and cells.

Antioxidants are used to neutralize the oxidants and make them less harmful. Foods that are rich in antioxidants include prunes, kidney beans, artichokes, and various types of berries. As the Maritimes are well-known for their blueberries, it was an inevitable theory – more blueberries, less hypertension?

After performing an eight week experiment on two groups of rats (those being fed a diet of blueberries and those who weren’t), Kevin and his colleagues found this to be to true. By testing the urine of the rats, they recorded that those on the blueberry diets had less oxidants being expelled.

Kevin noted how it was the first time he felt as though he was doing something for the betterment of human health. He had a personal connection to the topic as well.

“My own father had a stroke and a heart attack in his thirties, and more recently experienced his second heart attack, which was followed by triple bypass surgery. He survived all of these events, but I had first-hand experience with the impacts that cardiovascular disease can have on a family,” Kevin says. “So, that was very special to me to be working on something that could help prevent others from experiencing what my father had to go through.”

Not long after finishing this study, fate once again led Kevin where he never thought he would go. Although he planned to spend his life working as a “lab junkie” conducting research, he was lucky enough to land a nine-month teaching position at the Mount in 2009. Now eight years later, he works at the Mount as the Senior Biology Lab Instructor which, he emphasizes, is a wonderful experience and by far his favourite career yet.

Kevin offers this advice to those starting out on their academic journey: “Take time in life to figure out what you love to do. I knew that I wanted a career in science, but had no idea what direction I should take. I exposed myself to lots of different fields and took any good science opportunity I could for years. That’s why I still consider myself a jack of all trades. No-one should commit themselves to a career unless they know that they’re going to love it.”