“I wanted a place that the survivors and anyone who was connected to Mom could come to gather.”

Born and raised near the Mi’kmaq community of Millbrook First Nation, Natalie Gloade is passionate about education and community building.

At age 53, with the support of her friends and family, Natalie decided to complete her Master of Education in Lifelong Learning at the Mount. Students in the program engage with theories of how learning occurs, enhance their skills as teachers, program developers, and curriculum experts, and deepen their understanding of issues like diversity, inclusion, globalization, and evolving technologies.

“My daughter pushed me to continue to further my education. She was very supportive of me telling our family story. My husband also felt that this was something I should do to get my mother’s story out in the real world with the truths about who she was and how she lived. It hasn’t always been easy but the people around me have helped me along the way.”

“My daughter pushed me to continue to further my education. She was very supportive of me telling our family story. My husband also felt that this was something I should do to get my mother’s story out in the real world with the truths about who she was and how she lived. It hasn’t always been easy but the people around me have helped me along the way.” Natalie’s mother, Nora Madeline Bernard, was one of the many children sent to a residential school in Shubenacadie in 1944. At the time, Nora was nine-years-old and her two younger sisters were seven and eight. Natalie recounts the pain and mistreatment her mother experienced during this time.

“The nuns reassured Grammy Cope-Bernard that they were going to take care of the children. She told them they would be well fed and educated, with the understanding that their Mi’kmaq language would carry on. Once the door shut, they were scrubbed down with lye soap, their hair was cut, they were put in a uniform and forbidden to speak their language. They were abused, beaten, punished with straps and rulers. The Mi’kmaq culture was ripped from them. Their identity was taken and they were trying to beat the native out of the native.”

Natalie feels she has a role to play in bringing awareness to her mother’s story and the pain that still remains among her people. “We still feel the wrath of what happened. People need to know that this was real and that it did happen. The school system must incorporate the horrific Indian Residential School era as part of the curriculum. We must teach it and talk about it. We have to start somewhere and to pass on the lineage, the culture and the indigenous ways of knowing and being.”

“We as a society, as a culture and as a community have to heal. We have to help our sisters and our brothers to move forward to a better way of learning, loving and accepting.”

— MEd student Natalie Gloade

Creating a gathering place

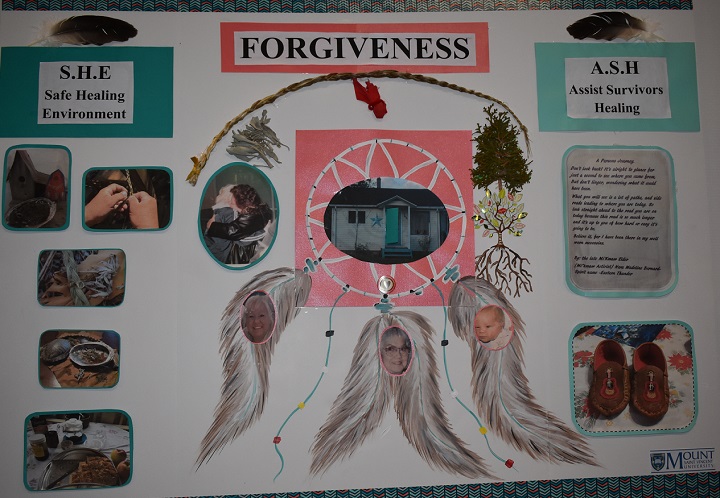

In an effort to honour her mother who was murdered at 72 years of age, Natalie decided to do her MEd practicum at her mother’s home. A key component of the adult education practicum is allowing students to contribute to their world and to grow and develop as critically reflective practitioners. Knowing this, Natalie decided to open up her mother’s home as a place for community to gather and to heal.

“I wanted a place that the survivors and anyone who was connected to Mom could come to gather. I was trying to simulate what Mom had done in the community, but I wanted to help people with their own healing process through healing circles, tea, traditional foods, smudging, strands of sweet grass, sage, cedar and tobacco. When people came to Mom’s, they always knew they had a place to eat, to have a nap, a place to divulge their pain and cry out their pain. She was their ear, their heart, their shoulder to cry on and her loving arms would wrap around them to give them comfort, along with a gentle whisper of strength.”

Nora Madeline Bernard spent much of her life advocating for the rights of Indigenous People. An estimated 79,000 residential school survivors received compensation thanks to a lawsuit that Bernard brought against the government in 2006 for her mistreatment.

Healing through connection with community

Through Natalie’s practicum, she was able to connect with residential school survivors to continue to celebrate her mother’s life. She also felt it was a way to bring awareness to the indigenous ways of life by incorporating cultural artifacts.

“It was all about reinforcing forgiveness and being able to talk about the residential school system. We as a society, as a culture and as a community have to heal. We have to help our sisters and our brothers to move forward to a better way of learning, loving and accepting. Forgiving is a choice. We are not forgiving because we accept and support what was done. We are forgiving because we have to do that so we can grow and move forward on Mother Earth’s journey of life. It’s about opening our hearts up and loving.”

Natalie credits the professors at the Mount with fostering an environment of inclusion and allowing students to explore their interests and talents. “There is a willingness from the professors to simplify things. They do not put words in your mouth and they help you bring your own voice out. They are there to support you, guide you and mentor you.”

Natalie credits the professors at the Mount with fostering an environment of inclusion and allowing students to explore their interests and talents. “There is a willingness from the professors to simplify things. They do not put words in your mouth and they help you bring your own voice out. They are there to support you, guide you and mentor you.”Although she feels that there is still work to be done in terms of bringing indigenous teachings into the classroom, Natalie feels the Mount is making good strides. “Dr. Jim Sharpe and other notable Doctorates at the school are bringing the indigenous culture into the walls that connect all of us studying at this incredible university. Mount Saint Vincent is a welcoming environment for our people to come and to receive a higher education. We have to thank MSVU for making steps to honour our sisters.”

When asked what the word ‘community’ means to her, Natalie responds saying “Community is the environment I live, learn and socialize in. It is a place where I want to feel safe, to be me and to be able to express myself.” This way of thinking is something that Natalie tries to foster in her classroom as a substitute teacher and in through her experiences as an adult learner.

This spring Natalie will graduate from the Mount with her Master of Education in Lifelong Learning – a degree that she never dreamed she would complete. She credits her family for their ongoing support and words of encouragement. “I didn’t think I was smart enough and my husband Ricky told me that I could do it. It has been an awesome experience.”

Natalie has plans to publish a book about her mother’s story. She will also continue to advocate for indigenous rights and hopes that a space on campus may someday be dedicated to her late mother Nora Bernard as a safe haven to smudge, to read and to reflect.