Meet Dr. Cecilia Alstrom-Rapaport

By Emily Albert, Mount student Some may not think that a PhD in plant breeding sounds very exciting, but the experiences Cecilia Alstrom-Rapaport has had as a result of just such a degree are far from mundane.

Some may not think that a PhD in plant breeding sounds very exciting, but the experiences Cecilia Alstrom-Rapaport has had as a result of just such a degree are far from mundane.

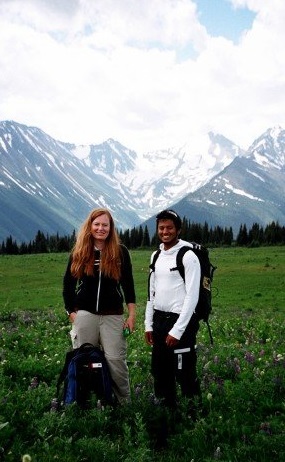

Students at Mount Saint Vincent University know Cecilia as a professor of statistics, but she’s travelled across Scandinavia, climbed to remote mountain meadows in British Colombia, Canada, and encountered grizzly bears – all while conducting research in plant genetics.

Out of all the experiences she’s had and places she’s been as a researcher, Cecilia says that the most amazing was when she was researching willow plants in remote regions of British Colombia.

“I had to pinch myself to say ‘I get paid to do this’,” Cecilia says. “It’s a nice beautiful day, I’m 2,000 meters up, and you look down at the small little villages below, and every year it was almost like a high to be up there to do the research.”

Cecilia and a group of her graduate students would travel to research sites in two main locations in British Columbia. There, they would locate and study multiple species of willows from two different types of willow plants – one that grew high up in the mountains (alpine, or arctic, willows) and another that grew along rivers (riparian willows). The idea, Cecilia says, was to learn more about how these populations are structured genetically in order to better protect them from extinction.

Finding ways to protect willow plants is important, as the plants have a variety of uses. Because riparian willow plants grow quickly, and can regrow after they have been cut down, they are an efficient source of fuel. In Europe, they are grown on farms for the specific purpose of being burned for energy. Riparian willows are often planted along rivers and streams in Canada and abroad to prevent erosion. Some species of willow have been used in medicines. But willows, like other plants, are susceptible to climate change. The alpine willows, which are accustomed to colder climates, are especially vulnerable.

Finding ways to protect willow plants is important, as the plants have a variety of uses. Because riparian willow plants grow quickly, and can regrow after they have been cut down, they are an efficient source of fuel. In Europe, they are grown on farms for the specific purpose of being burned for energy. Riparian willows are often planted along rivers and streams in Canada and abroad to prevent erosion. Some species of willow have been used in medicines. But willows, like other plants, are susceptible to climate change. The alpine willows, which are accustomed to colder climates, are especially vulnerable. “Maybe they [the alpine willows] will disappear,” Cecilia says, “and if we don’t know the genetic diversity or the genetic structure of these populations – how they reproduce, what they are dependent on and so on, maybe we will not be able to save them.”

“I’m doing something that people would almost pay to do, and I get paid to do it.”

— Dr. Cecilia Alstrom-Rapaport on her research adventures into the British Colombia wilderness

Cecilia and her team of researchers explored whether the willow plants in British Colombia are more likely to reproduce sexually, through seeds, or asexually, by growing new plants from along the length of their roots or from stems that had come in contact with the ground. Little had been done to study the frequency of each type of reproduction in Canada. Cecilia also studied factors such as the most frequent methods of willow pollination. While the research team studied the same factors at both the alpine sites and the river sites, the two regions had some differences.

“Up on the mountains it was beautiful, and you have these alpine meadows, and there you will have willows that are just a few inches high. So when they flower it is just like one or two enormous catkins that are kind of overshadowing the rest of the plant,” Cecilia says.

“Up on the mountains it was beautiful, and you have these alpine meadows, and there you will have willows that are just a few inches high. So when they flower it is just like one or two enormous catkins that are kind of overshadowing the rest of the plant,” Cecilia says.“It was not so amazing to do our research along the rivers because there’s tons of grizzly and black bears, so it was very, very nerve-wracking.” She notes that everyone had to carry at least two cans of bear spray in case they released the first one at the wrong time.

Once, she says, they were driving along a remote logging road on the way to the research site with a grizzly bear and her cubs running right in front of the car.

“My student was driving, and she was like ‘I don’t want to stop, I’m too scared to stop!’ And she was worried that if we stopped that the mom, who had two cubs, was going to be very aggressive,” Cecilia says. “So she just kept driving, and they just kept running in front of us.”

There were other complications with the research sites by the rivers as well. Originally from Sweden, Cecilia had forgotten to consider how, in Canada, beavers might affect the study.

“I hadn’t even thought about beavers. Because in Sweden we didn’t have any beavers – at the time, they hadn’t been reintroduced yet – so that was never anything I thought about,” Cecilia says.

After all of their hard work locating and marking each of the individual plants they were going to use in the study, Cecilia and one of her grad students returned to the river location to find that many of the plants they had so painstakingly selected were gone.

“There was one place, I have a picture, there’s one beaver lodge where you can see like ten of these branches with my tags on them stuck into the beaver lodge, and there of course they had started to sprout, so they were alive but we couldn’t get to them – they were out in the middle of the river on the beaver lodge,” Cecilia says. “It was such a nightmare.”

“There was one place, I have a picture, there’s one beaver lodge where you can see like ten of these branches with my tags on them stuck into the beaver lodge, and there of course they had started to sprout, so they were alive but we couldn’t get to them – they were out in the middle of the river on the beaver lodge,” Cecilia says. “It was such a nightmare.”The mishap set the study back, and one of Cecilia’s students ended up doing research on beavers while they were still studying willows. Cecilia says that with field work comes some unpredictability, and twists in the path.

“When you’re doing field work – that is that type of field work – it can suddenly take off in all sorts of directions,” She says, “It’s seldom just a straight road.”

Cecilia says that this part of her research experience has given her a new perspective from the one she had during her earlier education.

“When I was a math student I was very oriented on, you know, ‘there’s a question, and here’s the right answer.’ You know, like many students ask now: ‘What’s the right answer, we want to get the right answer.’ While as a researcher, it doesn’t work that way,” she says.

She explains that with research, one conclusion may seem the most logical for a while – but it is rarely correct indefinitely. Eventually, when other researchers publish more papers on the topic and more information becomes available, the original conclusion may no longer fit all the available evidence.

“When you ask a question, it can be millions of different answers, and it’s not necessarily that one is correct. One is correct right now and then when you get more information, that may actually be incorrect and we have some other, more correct answer or something that is closer to the truth. And that builds new questions.”

“But if you see that a student understands something, then you have your results and rewards right there and then.”

— Cecilia on the rewards of teaching over research

Today, Cecilia teaches part-time at the Mount and Dalhousie University. While this may seem far removed from dealing with bears and beavers in the field, Cecilia says that the experiences that she’s had as a researcher have given her real-life scenarios that she can use as examples, helping her to make statistics more engaging for her students.

“It does play in, in the sense that I didn’t study statistics only theoretically. Also, when I did take statistics, I thought it was extremely boring,” Cecilia says. “I’ve tried to introduce more stuff to make it more fun.”

Does she miss the excitement of research? Maybe. But Cecilia is incredibly glad for the opportunities she has had, and equally happy to be teaching. Cecilia’s research in plant genetics has been anything but ‘boring’, and has given her some amazing experiences. But her work as a professor has perhaps been even more rewarding. In a way, she may even prefer the role of teacher to the role of researcher.

“All the time [when doing research] I was sort of pinching myself thinking ‘I’m doing something that’s really fun’, you know, all the time. Not everything was fun. But I’m doing something that people would almost pay to do, and I get paid to do it,” she says.

“In the end, I think I’m a much better teacher actually than I am a researcher. Because you have to be structured to be a researcher – you have to keep at it and if you don’t get your article published, you just need to revise a little bit, and keep sending it in, and I don’t have that patience.”

“But if you see that a student understands something, then you have your results and rewards right there and then.”